With the advent of the shale oil revolution, the significance of some traditional oil and gas lease provisions, such as the shut-in royalty provision, have been recently neglected. As a result, landmen may be asking themselves, “What is the shut-in royalty provision and will it ever impact a lease taken in an oil play?” The resounding answer is YES! Although a more traditional tool for gas plays, a shut-in royalty provision may apply to either a gas or oil well depending on the language used.

What is this thing anyway?

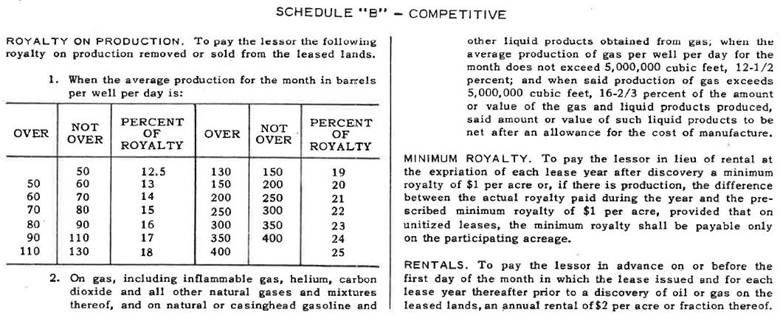

Nearly all oil and gas leases include a habendum clause,1 which allows a lease to be held in effect for a period of time and so long thereafter as oil and gas is produced in paying quantities. However, production can cease or be temporarily suspended for a number of reasons. Without a savings clause, even a brief a cessation in production would cause a lease past its primary term to expire. In light of this, lessees developed the shut-in royalty provision, among other savings clauses. Essentially, the shut-in royalty provision allows a lessee to temporarily cease production (i.e., shut-in a well) and pay a shut-in royalty to the lessor in place of the royalty on production that is not occurring during the shut-in period. The following is a typical, older shut-in royalty provision, created specifically for a gas well:

[W]here gas from one or more wells producing gas is not sold or used, lessee may pay as royalty $500.00 per year, and upon such payment it will be considered that gas is being produced within the meaning of Paragraph 2 [the habendum clause] hereof.2

The following is another, older example, used for either an oil or gas well:

This lease shall continue in full force for so long as there is a well or wells on leased premises capable of producing oil or gas, but in the event all such wells are shut in and not produced by reason of the lack of a market at the well or wells, by reason of Federal or State laws, executive orders, rules or regulations, or for any other reason beyond the reasonable control of Lessee, then on or before such succeeding anniversary of the date hereof occurring ninety (90) or more days after all such wells are so shut in and after the expiration of the primary term and prior to the date production is commenced or resumed, or this lease surrendered by Lessee, Lessee shall pay to Lessor as royalty an amount equal to the annual rental hereinabove provided for.3

There are numerous variations of the shut-in royalty provision, many of which may not be ideal for the lessee’s operations. For example, the provision might be focused on shutting-in a well for the purpose of finding a buyer of natural gas, dewatering a coalbed methane well, or repairing broken-down equipment. Although this article cannot discuss all of the variations, there are numerous additional resources on this subject.4

Aww shucks, the crank broke again!

Although the shut-in royalty provision may have been historically created to protect a lessee in the event that there is a lack of a market for gas, a lessee might use it for numerous other reasons. Some additional causes include: governmental restrictions, inability to economically produce the leased substances, lack of available linear infrastructure, equipment failure, or Force Majeure.5 Many older shut-in royalty provisions provide specific reasons to shut-in a well, while most newer versions are silent on the matter. If silent, a court will determine whether or not the cause for the temporary cessation was reasonable. While there is comfort in expressly describing the allowed causes for the temporary cessation, this could potentially lead to an unfavorable outcome for the lessee. Unless the lessee is aware of certain circumstances that might occur, the better approach may be to choose a shut-in royalty provision that allows the lessee to use its good faith judgment. In any event, it should be noted that some courts have required a well to be physically able to produce if it were turned on, based on the historic development of this clause (but see the discussion below under shale oil).6

Uh… did we pay that shut-in royalty on time?

Many older shut-in royalty provisions require the payment of a shut-in royalty to be paid in order for the lease to be considered held by production (e.g., the first example above). Over time, lessees realized that structuring the shut-in royalty payment as a condition may cause the lease to expire if the payment is not timely made.7 As a result, newer versions structure the shut-in royalty provision as a covenant rather than a condition. In other words, the existence of a shut-in well maintains the lease in effect, not the payment of the shut-in royalty (e.g., the second example above).

If the shut-in royalty provision is silent regarding the timing of payment (e.g., the first example above), a court will determine a reasonable time.8 If the shut-in royalty provision provides the timing of payment, it typically does so by using a specific time period (e.g., within 90 days), a specified date (e.g., on the anniversary of the lease date), or a combination of both (e.g., on the next anniversary date of the lease occurring 90 days after the well is shut-in, such as in the second example above). Generally, it is more practical to expressly provide the timing of payment and for such timing to be after the well is shut-in so that the shut-in provision won’t be triggered if the well is only shut-in for a brief period of time.

Wait, you mean that “oll” company can hold my lease forever?

Arguably, a lessee is expected to resume production from a shut-in well within a reasonable time. However, in order to avoid potential disputes and to limit what is a reasonable time period, mineral owners developed additions to the shut-in royalty provision. The following examples are illustrative:

Notwithstanding the provisions of this section to the contrary, this lease shall not be continued after ten years from the date hereof for any period of more than five years by the payment of said annual royalty;

[P]rovided, however, that in no event shall Lessee’s rights be so extended by shut-in royalty payments for more than two (2) years beyond the primary term; or

[T]he Lessee may extend this lease for two (2) additional and successive periods of one (1) year each by the payment of a like sum of money each year on or before the expiration of the extended term.9

Such additions to the shut-in royalty provision may prove useful in the event the parties to the lease cannot agree on whether or not a shut-in royalty provision should be included in the lease.

I can’t use this for horizontal oil wells, can I?

Okay, it’s finally time to answer the question, “What about the shale oil revolution – can we use the shut-in royalty provision for wells awaiting completion?” Because such a well is not capable of producing, typical shut-in royalty provisions won’t apply. The good news is that this can be easily fixed by expanding the term “capable of producing quantities” (after ensuring that the provision covers oil as well as gas).10 For example, a lessee could add the following after the shut-in royalty provision:

A well that has been drilled and cased shall be deemed capable of producing oil and gas in paying quantities, notwithstanding the fact that any such well has not been perforated, fractured, or otherwise completed.11

If the parties can’t agree on this broad expansion, the timing for such uncompleted wells could be limited (e.g., “…shall be deemed capable of producing oil and gas in paying quantities for a period not to exceed 180 days…”).12 Alternatively, the parties could agree to limit the expansion to specific types of wells (e.g., shale wells, coalbed methane wells, or horizontal wells).13

Fine. Just tell me which form of shut-in royalty provision to use.

As previously discussed, there are numerous forms and variations of the shut-in royalty provision. Of course, there is no one-size-fits-all. The shut-in royalty provision used in a lease form should be carefully selected to meet the needs of the lessee’s operations and regularly modified as technology advances and oil and gas plays shift. Although it won’t apply to all scenarios, the following example appears to embrace most of the key concepts discussed in this article:

If after the primary term one or more wells on the leased premises or lands pooled or unitized therewith are capable of producing Oil and Gas Substances in paying quantities, but such well or wells are either shut in or production therefrom is not being sold by Lessee, such well or wells shall nevertheless be deemed to be producing in paying quantities for the purpose of maintaining this lease. If for a period of 90 consecutive days such well or wells are shut in or production therefrom is not sold by Lessee, then Lessee shall pay an aggregate shut-in royalty of one dollar per acre then covered by this lease. The payment shall be made to Lessor on or before the first anniversary date of the lease following the end of the 90-day period and thereafter on or before each anniversary while the well or wells are shut in or production therefrom is not being sold by Lessee; provided that if this lease is otherwise being maintained by operations under this lease, or if production is being sold by Lessee from another well or wells on the leased premises or lands pooled or unitized therewith, no shut-in royalty shall be due until the first anniversary date of the lease following the end of the 90-day period after the end of the period next following the cessation of such operations or production, as the case may be. Lessee’s failure to properly pay shut-in royalty shall render Lessee liable for the amount due, but shall not operate to terminate this lease.14

Depending on the circumstances, the parties to a lease may desire to expand the term “capable of producing quantities” for an incomplete well or limit the maximum amount of time a well may be shut-in, as each is discussed above.

1See, generally, Trent Maxwell, The Habendum Clause – ‘Til Production Ceases Do Us Part,’ available at http://www.hollandhart.com/lease-provisions-part-2/.

2From a midcontinent form discussed in Patrick H. Martin & Bruce M. Kramer, Williams & Meyers, Oil and Gas Law § 631 (2014).

3Id.

4See Martin & Kramer, supra note 2 at §§ 631 et seq.; John S. Lowe, “Shut-in Royalty Payments,” 5 Eastern Min. L. Inst. 18 (1984); Robert E. Beck, “Shutting-In: For What Reasons and For How Long?,” 33 Washburn L.J. 749 (1994); David E. Pierce, “Incorporating a Century of Oil and Gas Jurisprudence into the ‘Modern’ Oil and Gas Lease,” 33 Washburn L.J. 786 (1994); Thomas W. Lynch, “The ‘Perfect’ Oil and Gas Lease (an Oxymoron),” 40 Rocky Mt. Min. L. Inst. 3 (1994).

5See Martin & Kramer, supra note 2 at § 632.4.

6See, e.g., Hydrocarbon Mgmt., Inc. v. Tracker Exploration, Inc., 861 S.W.2d 427 (Tex. Ct. App. 1993); see also Milam Randolph Pharo & Gregory R. Danielson, “The ‘Perfect’ Oil and Gas Lease: Why Bother,” 50 Rocky Mt. Min. L. Inst. 19 (2004).

7See, e.g., Freeman v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 171 S.W.2d 339 (Tex. 1943); see also Pharo, supra note 6.

8See Martin & Kramer, supra note 2 at § 632.6.

9See Martin & Kramer, supra note 2 at § 632.13.

10John W. Broomes, “Spinning Straw into Gold: Refining and Redefining Lease Provisions for the Realities of Resource Play Operations,” 57 Rocky Mt. Min. L. Inst. 26, 26–5 (2011).

11Id. at 26–9.

12Id. at 26–10.

13Id.

14From the Modified Lynch Form. Pharo, supra note 6 at Appendix A.