In the context of federal oil and gas leases, the terms “communitization” and “unitization” are distinct concepts which are subject to different statutes, regulations, and procedures. As such, the method to “communitize” a federal oil and gas lease is different than the process used to “unitize” such leases. These respective differences are highlighted herein.

Communitization of Federal Oil and Gas Leases

Virtually all oil and gas producing states have promulgated minimum acreage requirements for the drilling of oil or gas wells.[1] The United States recognized the importance of state conservation statutes, and accordingly passed an amendment to the Mineral Leasing Act which allowed federal lessees to conform to state well spacing orders through a communitization agreement.[2] Communitization is the agreement to combine small tracts, of which one or more is federal or Indian lands, for the purpose of committing enough acreage to form the spacing/proration unit necessary to comply with the applicable state conservation requirement and to provide for the development of these separate tracts which cannot be independently developed in conformity with said conservation requirements.[3] In essence, communitization is the federal equivalent of pooling the lands in a spacing/proration unit under state law. The common thread of all federal communitization agreements is that at least one federal or Indian lease or tract must be involved.[4] That federal or Indian lease is communitized with other leases that may be federal, Indian, state, or fee.[5]

Although there is no prescribed form for a federal communitization agreement in the regulations, the regulations do require that certain information be included within the communitization agreement. There are relatively few requirements for communitization agreements, but the applicant must usually provide sufficient information so the authorized officer can make a determination that it would be in the best interests of conservation and of the United States for the federal leasehold to be communitized.[6] Specifically, the agreement must describe the separate tracts comprising the drilling or spacing unit, describe the apportionment of production or royalties to the parties, name the operator, contain adequate provisions for the protection of the interests of the United States, be filed prior to the expiration of the federal leases involved, and be signed by or on behalf of all necessary parties.[7] The BLM Manual 3160-9-Communitization includes a standard or model communitization agreement form, one for federal leases and one for Indian leases, which should be used whenever possible.[8]

The necessary parties include all working interest owners and lessees of record. A communitization agreement may be approved without joinder by the royalty, overriding royalty, and production payment interest owners, but this will result in different payment scenarios depending upon the location of a successfully completed well.[9]

If a state has them, the state’s compulsory pooling statutes may be utilized to commit a nonconsenting party’s interest to the communitization agreement; although, without the consent of the Secretary of the Interior, the state commission does not have jurisdiction to force pool unleased interests of the United States.[10] Copies of any compulsory/force pooling order should be furnished with and be part of the communitization agreement if such interest owner does not execute the agreement.[11] The authorized officer in the appropriate BLM office must approve, on behalf of the Secretary, the communitization agreement with respect to any included federal leases.[12]

Although not mandatory, the filing of a Preliminary Application for Approval to Communitize is recommended, particularly in instances where the model form of communitization agreement is not followed precisely.[13] The BLM Manual provides that a request for preliminary approval to communitize may be filed at any time with the authorized officer. It is also recommended that preliminary approval be requested if there is some doubt as to whether the proposed tracts are logically subject to communitization, or if there is any doubt as to whether a communitization of multiple zones will be approved. The preliminary approval procedure will expedite final approval and may avoid the necessity of extensive revisions and re-execution of a finalized communitization agreement.[14]

The BLM will not approve an agreement that purports to communitize all horizons from the surface down to the center of the earth.[15] However, if it is anticipated that the well will be completed in multiple formations, it is important to include all formations and horizons that are producing or may produce hydrocarbons intended to be allocated pursuant to the terms of the communitization agreement.[16] All communitized formations must be subject to the same spacing requirements and, where multiple and clearly distinct formations are covered by the same communitization agreement, the BLM Manual provides that Section 1 be amended to clearly state that the agreement shall apply separately to each formation as though a separate communitization agreement for each formation had been executed.[17] In the event a proposed well is projected to test multiple formations that are subject to different spacing requirements, separate communitization agreements should be submitted to BLM for each formation or set of formations with the same spacing requirements.[18]

The communitization agreement must be filed prior to the expiration of the federal leases to be communitized.[19] The regulations require that the communitization agreement be filed in triplicate with the proper BLM office.[20] If state lands are involved one additional counterpart must be submitted.

An executed counterpart of the approved communitization agreement, duly acknowledged, should be filed of record in the county in which the land is located. When fee leases are involved, the operator should record either the communitization agreement or otherwise comply with the terms of the pooling provision of any fee lease.[21]

In order to approve a communitization agreement, the Mineral Leasing Act requires that the Secretary determine communitization is “in the public interest”[22]:

The public interest requirement for an approved communitization agreement shall be satisfied only if the well dedicated thereto has been completed for production in the communitized formation at the time the agreement is approved or, if not, that the operator thereafter commences and/or diligently continues drilling operations to a depth sufficient to test the communitized formation or establish to the satisfaction of the authorized officer that further drilling of the well would be unwarranted or impracticable.”[23]

Communitization agreements usually provide for a term of two years and so long thereafter as communitized substances are, or can be, produced from the communitized area in paying quantities.[24] Assuming the public interest requirement is satisfied, any federal lease eliminated from an approved communitization agreement, or any federal lease in effect at the termination of the agreement, shall continue in effect for the original term of the federal lease or for two years after its elimination from the plan or termination of the agreement, whichever is longer, and for so long thereafter as oil or gas is produced in paying quantities.[25] No lease shall be extended if the public interest requirement has not been satisfied.[26]

Unitization of Federal Oil and Gas Leases

Unitization is the agreement to jointly operate an entire producing reservoir or a prospectively productive area of oil and/or gas. The entire unit area is operated as a single entity, without regard to lease boundaries, and allows for the maximum recovery of production from the reservoir. Costs are reduced because the reservoir can be produced by utilizing the most efficient spacing pattern, separate tank batteries are not necessary, and there is no requirement to drill unnecessary offset wells. The objective of unitization is to provide for the unified development and operation of an entire geologic prospect or producing reservoir so that exploration, drilling, and production can proceed in the most efficient and economical manner by one operator.[27]

The Bureau of Land Management is the administering agency for federal onshore units and has established procedures that must be followed to unitize federal lands.[28] Although not required by the regulations, the BLM strongly encourages an informal discussion with the authorized officer of BLM office having jurisdiction over the area where the lands are located concerning the proposed area of the unit, the depth of the test well and formation to be tested, and the form of agreement.[29] This should be done prior to filing of an application.[30] It is recommended that this is done in order to ensure the unit approval process moves smoothly.

BLM regulations provide that, to initiate the formation of a federal unit, an application for designation of a proposed unit area be filed in duplicate.[31] The application must be accompanied by a map or diagram outlining the area sought to be designated and indicating the federal, state, privately owned, or Indian lands by symbols or colors.[32] The plat must indicate the separate leasehold interests involved and identify them by serial number in the case of federal and Indian oil and gas leases.[33] It is advisable to show the ownership and expiration dates of each lease involved. The application must also be accompanied by a geologic report and it must indicate the zones that are to be unitized (if all zones or formations are not to be included).[34]

The owners of any interest in the oil and gas deposits to be unitized are proper parties to the unit agreement. All such parties must be invited to join the agreement.[35] This includes royalty owners and holders of overriding royalty interests and any other non-cost bearing interests in production, as well as working interest owners. Prior to approval, notice of the proposed agreement must be given to all parties with a request to join the agreement.[36] When state lands are to be unitized with federal lands, the unit agreement must be approved by the state prior to submission to the BLM for final approval.[37]

After the unit area has been designated and the unit agreement has been fully executed by the parties desiring to commit their interests to the unit, a minimum of four signed counterparts must be filed for approval with the proper BLM office.[38] These instruments should be accompanied by a request from the proponent for final approval of the unit, setting forth the acreage interests fully committed, effectively committed, partially committed, and not committed and show the percentage in each category.[39] A showing must also be made that all parties owning not committed interests within the unit area have been extended an invitation to join in the unit agreement and that a reasonable effort has been made to obtain the joinder of all such parties.[40] The request for final approval must include a list of the overriding royalty interest owners who have executed or ratified the unit agreement.[41] A tract will be considered “fully committed” if all interest owners have joined the unit and all working interest owners have also executed the applicable operating agreement.[42] A tract will be considered “effectively committed” to the unit without joinder by overriding royalty interest owners and will be treated identically as a “fully committed” tract, but, will result in different payment scenarios depending upon the location of the successfully completed unit well.[43] A tract will be considered “partially committed” if less than all of the lessors/royalty interest owners have joined, or all operating rights owners of a federal lease have joined but the record title holder has not.[44] Such partially committed tracts may be considered to be under the effective control of the unit operator, however, no unit benefits will accrue to the tract in the absence of actual operations on the partially committed tract or an allocation of production to that tract either from a well on the tract or from another location.[45] Finally, if any working interest owner in a tract does not commit its interest, that tract is deemed “not committed.”[46] BLM regulations provide that a unit agreement will not be approved “unless the parties signatory to the agreement hold sufficient interests in the unit area to provide reasonably effective control of operations.”[47] Generally, 85% of the tracts in the unit must be fully, effectively or partially committed to meet this “effective control” requirement.[48]

After four signed counterparts of the executed agreement are submitted, the authorized officer approves the unit agreement upon a determination that the agreement is necessary or advisable in the public interest and is for the purpose of more properly conserving natural resources.[49] A model federal onshore unit agreement for unproven areas (hereinafter “Model Form”) is included in the BLM regulations and promulgated to help implement these provisions.[50] Section 9 of the Model Form specifically provides for the commencement of an initial test well within six months after the effective date of the unit.[51] If a discovery is not made in the initial test well, provision is made for continuous drilling on unitized lands until a discovery is made provided that not more than six months elapse between the completion of one well and the commencement of the next.[52] Paying quantities for purposes of meeting the drilling obligations in section 9 is defined as quantities of unitized substances sufficient to repay the costs of drilling, completing, and producing operations, with a reasonable profit.[53]

Upon approval, the unit agreement becomes effective.[54] However, the public interest requirement is satisfied only if the unit operator commences actual drilling operations and diligently prosecutes such operations in accordance with the terms of the agreement.[55] If this requirement is not satisfied, the approval of the agreement and lease segregations and extensions shall be invalid.[56] Evidence of the approved unit should be recorded in the county records to impart notice.

Finally, it is important to understand the interplay between the unit agreement and the unit operating agreement because both agreements, taken together, constitute the unit arrangement and establish the contractual rights and obligations of the parties.

In addition to setting forth the terms and conditions for the unit, the unit agreement prescribes the method of allocating production for purposes of determining royalties, overriding royalties, production payments, and other non-cost bearing burdens, but does not dictate the working interest owners’ respective shares of production or the allocation of costs/royalty burdens associated therewith.[57] These, and other duties and obligations among the working interest owners, are matters covered by the unit operating agreement.[58]

The BLM does not prescribe any particular form of unit operating agreement and the working interest owners are generally free to use whatever form of unit operating agreement they prefer.[59] The unit operating agreement is entered into by the working interest owners who are committing their interests to the unit in conjunction with the execution of the unit agreement.[60] The interests of the royalty owners are not affected by the form of unit operating agreement chosen by the working interest owners.[61] Two copies of the unit operating agreement are required to be filed in the proper BLM office before the unit agreement will be approved.[62]

[1] Angela L. Franklin, Communitization Agreements in the 21st Century, Federal Onshore Oil and Gas Pooling and Communitization, Paper 3-4 (Rocky Mt. Min. L. Fdn. 2006) [hereinafter Communitization Agreements].

[2] See Mineral Leasing Act, Pub. L. No. 696, § 17(b), 60 Stat. 952 (1946).

[3] See 2 Lewis C. Cox, Jr., Law of Federal Oil and Gas Leases § 18.01 (2017).

[4] Communitization Agreements, supra note 2, at 3-5.

[5] Id.

[6] 1 Bruce M. Kramer & Patrick H. Martin, The Law of Pooling and Unitization § 16.04 (3rd ed. 2017).

[7] 43 C.F.R. § 3105.2-3(a) (2018).

[8] Communitization Agreements, supra note 2, at 3-5.

[9] Id.

[10] Id. at 3-6.

[11] Id.

[12] 43 C.F.R. § 3105.2-3 (2018).

[13] Communitization Agreements, supra note 2, at 3-7.

[14] See id.

[15] Id. at 3-8.

[16] Id.

[17] Bureau of Land Management, BLM Manual 3160-9-Communitization .11M (1988) [herein after BLM Manual].

[18] Communitization Agreements, supra note 2, at 3-8.

[19] 43 C.F.R. § 3105.2-3(a) (2018).

[20] Id. § 3105.2-1.

[21] Communitization Agreements, supra note 2, at 3-10.

[22] 30 U.S.C. § 226(m) (2018).

[23] 43 C.F.R. § 3105.2-3(c) (2018).

[24] See Section 10 of Model Form of a Federal Communitization Agreement in BLM Manual app.

[25] 43 C.F.R. § 3107.4 (2018). But see, R. E. Hibbert, 8 IBLA 379 (1972), GFS (O&G) 6 (1973).

[26] 43 C.F.R. § 3107.4 (2018).

[27] Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.01[2].

[28] Id. § 18.04[1].

[29] Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[2].

[30] See id.

[31] 43 C.F.R. § 3183.2 (2018)

[32] Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[3] (citing 43 C.F.R. §§ 3181.2, 3183.2).

[33] See id. § 18.04[3].

[34] See 43 C.F.R. § 3181.2 (2018).

[35] 43 C.F.R. § 3181.3 (2018).

[36] See Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[4].

[37] 43 C.F.R. § 3181.4(a) (2018).

[38] 43 C.F.R. § 3183.3 (2018).

[39] See Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[6].

[40] Id. (citing 43 C.F.R. § 3181.3).

[41] See Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[6].

[42] See Frederick M. MacDonald, Preparing and Finalizing the Unit Agreement: Making Sure Your Exploratory Ducks are in a Row, Federal Onshore Oil and Gas Pooling and Communitization, Paper 8-23 (Rocky Mt. Min. L. Fdn. 2006).

[43] Id. at 8-24.

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] Id. at 8-25.

[47] 43 C.F.R. § 3183.4(a) (2018)

[48] MacDonald, supra, at 8-16.

[49] See Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[6]. (citing 43 C.F.R. § 3183.4).

[50] See Thomas W. Clawson, Paying Well Determinations, Federal Onshore Oil and Gas Pooling and Communitization, Paper 11-3 (Rocky Mt. Min. L. Fdn. 2006).

[51] See Model Form, § 9, 43 C.F.R. § 3186.1.

[52] See Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.03[2][b][iii].

[53] Model Form, § 9, 43 C.F.R. § 3186.1.

[54] Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[6] (citing Lario Oil & Gas Co., 92 IBLA 46, GFS(O&G) 54 (1986)).

[55] Kramer & Martin, supra, § 18.04[7].

[56] 43 C.F.R. § 3183.4(b) (2018).

[57] See Steven B. Richardson and Lynn P. Hendrix, The Unit Operating Agreement for Federal Exploratory Units, Oil and Gas Agreements: Joint Operations, Paper 13-3 (Rocky Mt. Min. L. Fdn. 2008).

[58] Id.

[59] Id. at 13-1.

[60] Id. at 13-3.

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

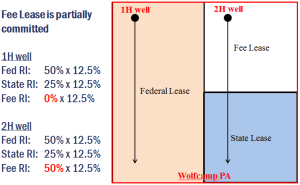

So what happens if the lessee’s working interest is committed to the unit agreement, but the lessor’s royalty interest is not? While the lessee will be allocated proceeds according to its proportionate share of the unit production area, the lessor will be allocated proceeds on a leasehold basis. This can result in a windfall either for the lessor or the lessee (compare the allocation of proceeds from the 1H and 2H wells in the diagram to the right, assuming 320 acre standup spacing units).

So what happens if the lessee’s working interest is committed to the unit agreement, but the lessor’s royalty interest is not? While the lessee will be allocated proceeds according to its proportionate share of the unit production area, the lessor will be allocated proceeds on a leasehold basis. This can result in a windfall either for the lessor or the lessee (compare the allocation of proceeds from the 1H and 2H wells in the diagram to the right, assuming 320 acre standup spacing units).